Does AI Work? Some Thoughts on Speed-Accuracy Tradeoffs, AI, and Deskilling

Published:

Does AI actually work? Is it fake? I want to put a little tool for thinking about that question into the box, one that I’ve been finding useful. In behavioral sciences, there is a ubiquitous effect, found in all kinds of situations: a speed-accuracy tradeoff. I’ll take that concept and use it to complicate the question “Does AI actually work?” in a way that will, I hope, make it easier to see what kind of project AI really is.

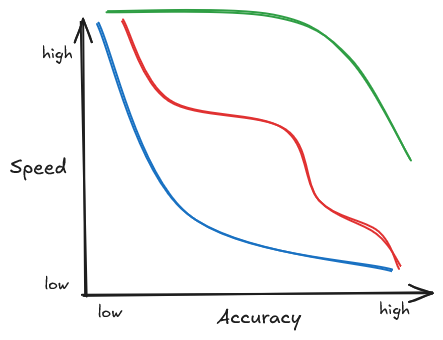

So, what is a speed-accuracy tradeoff? Well, take some task, maybe a well-studied one from somewhere close to my own academic background, a so-called lexical decision task. We put some series of letters on a screen, and then ask people if this is a word (in English, or perhaps some other language that the person knows). As you might imagine, people who can read are usually quite excellent at deciding whether a sequence of letters is a word, or what we’d call a nonce word. But as you might also imagine, if we give them less and less time, forcing them to make the decision ever faster, there comes a point where performance starts to deteriorate. And the faster they have to be, the more “mistakes” people make. In other words, there is a tradeoff between speed and accuracy. Such speed-accuracy tradeoffs are ubiquitous, they’ve been studied for myriad tasks, and for humans and animals alike. Different tasks will obviously differ (even differ dramatically) in their particular tradeoffs, but we can visualize the general idea in a plot that shows some kind of negative correlation between speed and accuracy. The particulars may vary quite a bit, so here’s some examples of what the tradeoffs could look like:

As a general rule (or at least a general rule of thumb), higher accuracy implies lower speed, and higher speed implies lower accuracy. If we want to put it in mathematical terms, we can say these functions are all downward monotonic. That is, they only ever fall or stay flat, but we don’t usually get situations where the curve moves upwards, i.e., where an increase in speed would correlate with an increase in accuracy (and we’ll certainly ignore that possibility for the purpose of this blogpost). That is, after all, why we call it a tradeoff – more speed implies less accuracy, and higher accuracy implies a lower speed.

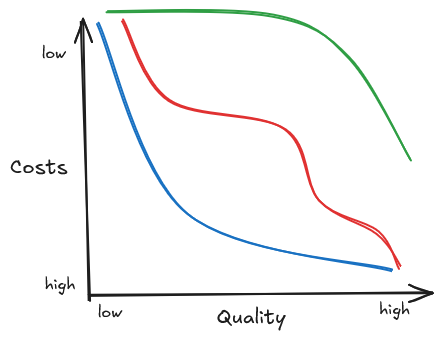

Now, we can generalize this a bit: if you want something done to a higher degree of precision, a higher level of (average) quality, and so on, it’ll take more time. Or perhaps, it costs more money – two things that are decidedly not the same, but which can look the same on a company balance sheet (and hence “to capital”, as seen through the logic of capital, etc). So let’s call it a cost-quality tradeoff. Again, any such curve will be highly task specific – some things take a long time, some things take only a little. Some things improve rapidly in quality when you take just a little extra time, others take a lot of time for just a small amount of improvement. Improvements aren’t equally distributed – perhaps the first extra minute I give myself helps a lot, but the second minute only marginally improves the outcome. And so on. But we’re in the realm of the vague and abstract, so let’s just assume that cost-quality tradeoffs can be characterized as a downward monotonic function (one that only ever falls or stays flat). So we could relabel our speed-accuracy graph like this:

Perhaps a little confusingly, I’ve now labeled costs as going from high to low. That’s because low speed (taking a lot of time) is expensive. If a worker takes an hour to do a task, they have to be paid twice as much as if they only took half an hour, and so on. This way of drawing it also has the advantage that both the cost axis and the quality axis to go from less to more desirable (certainly more desirable for capitalists, managers, etc): high costs are less desirable than low costs, and low quality is less desirable than high quality. At least all else being equal - after all, we’re talking about a tradeoff.

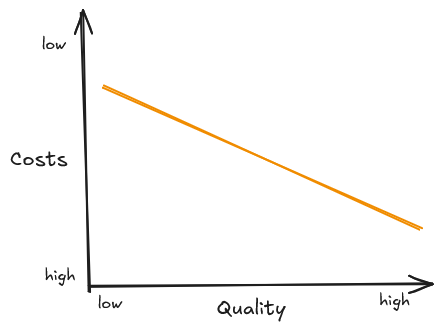

Now, we’re not focused in the ways different tasks differ, right now, so let’s do another somewhat silly but hopefully innocent simplification, and represent the cost-quality tradeoff in general as a generic downward sloping line.

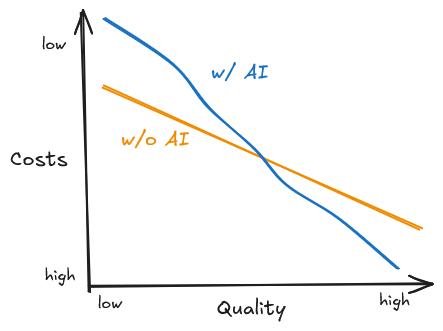

Alright, our imaginary world is super simple now, so let’s finally introduce some artificial intelligence. Let’s assume that the previous graph is the “before AI” description of some work task. Time to wonder how AI might affect the curve. First, let’s disregard the AI-booster scenario (“Yes, of course AI works, yay, it works even better than humans!!”): in such a scenario, AI could help achieve higher quality at lower costs, shifting the cost-quality trade-off across the board. Certainly, AI “doesn’t work” in that regard. So, a clear nod of agreement in that way to all my friends who rightly love to debunk and deflate the lies and exaggerations of AI peddlers. But I think a picture that is both clearer and more discomforting emerges when we move beyond that particular binary yes/no question of “Does AI work?”. The trade-off doesn’t require a uniform answer across the board, but instead it does something stranger. I suspect that for plenty of “economically valuable” tasks (as those eye-roll-inducing AGI descriptions have it) the comparison looks something like this:

This is a scenario where low(er) quality output gets significantly cheaper, even if AI does not help with high quality output – in the graph sketched, we even assume that beyond a certain quality requirement AI-assisted output is more expensive rather than less expensive. It certainly isn’t trivial to find the transition point between those, and plenty of bad things will come just from misidentifying it. Quite regardless, I think that surely, the massive amount of AI slop and AI scams already in existence suggests that something like this is happening already – the low quality end of plenty of textual/visual/coding/etc production has already gotten so much cheaper that tons more of it are getting churned out.

But what about the realm beyond scams and slop? What about realms of the economy that don’t depend on fraud but on actually producing things or services? Well, it may be useful to ask whether there were other, similar kinds of curve-shifts before AI. In Why We Fear AI, we argue that the most obvious comparisons are things like fast fashion, or furniture (IKEA etc): some player introduces goods that are a) significantly cheaper, and b) somewhat lower quality than the previously existing mid-level goods. As a consequence, the mid-level market gets outcompeted and less durable goods crowd out much of the mid-quality market with low prices. As a consequence, the goods that are available are increasingly concentrated on either the high end, or around a relatively narrow band on the low-mid level quality. So, the IKEA/fast fashion model of market capture implies a kind of bifurcation of the available goods, both in terms of quality and in terms of costs: furniture that can survive a few moves or shoes that last 5+ years out of reach for many people at the lower end of the income spectrum, the goods that are affordable need to be replaced frequently, etc. From furniture to shoes, from pans to shirts, lots of stuff has gotten a lot cheaper and kinda shittier over the last few decades. I’ll leave the exploration of the obvious similarities with Cory Doctorow’s enshitification concept aside for another time. Instead, here’s another pair of graphs of a hypothetical situation like this.

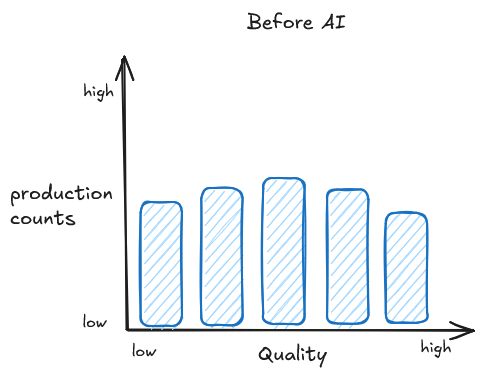

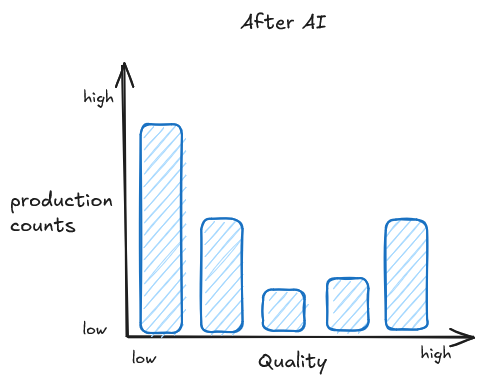

In the before AI time, let’s assume that all qualities are produced roughly evenly. Maybe there’s a little bit of a very flat normal distribution, who knows. The point, at any rate is the change: I’d expect the middle quality (where AI stops helping) to be crowded out – the lower quality is just getting cheaper at a much faster rate, and so it can (like fast fashion) outcompete the mid-level quality on price. AI may be “mid”, but it’s effects will be anti-medium-quality. So after AI, we can expect a shift like this, with the medium level quality crowded out (and less clear effects on the higher quality – though I suspect that decreased competition from medium quality goods will often end up increasing the price of the higher quality goods.)

What about the effects on labor? Both in these older cases of physical commodities and in the current case of AI, the moves are, to a significant degree, predicated not on increased productivity, but on the replacement of skilled (high paid) labor with less skilled labor. The more or less artisanal carpenter gets replaced by a factory worker, and all the usual methods of scientific management are applied, labor intensity increases, wages decrease (certainly relative to the production, likely also in absolute terms). As we argue in our book in a lot more detail, AI, especially generative AI, is (among many other things) a technology for deskilling, for transforming tasks within a production into tasks that can be performed with less/cheaper training, and thus for lower pay. I’ll just quote a short section from our book about the effects we can expect:

Most work that can be deskilled by generative AI will be increasingly gigified, while a small section of specialists will produce AI-free and “artisanally” for the upper crust. So-called self-driving cars already operate on a mix of automation and gig-work. The “autonomous” vehicles of General Motors subsidiary Cruise, for instance, are remotely assisted some 2–4 percent of the time, or every 2.5–5 miles, with their human “autonomous vehicle operators” continually monitoring many cars simultaneously. The rich, of course, have their driving produced artisanally already — by chauffeurs. AI tutors will be running on language models, but just as with Amazon’s warehouse surveillance and autonomous cars, AI tutoring will also be supported by a hidden underclass of deskilled gig-workers that monitor the chat windows of dozens of students at the same time. Meanwhile, the wealthy will continue to hire Ivy League PhD students to look after their children.

The legal domain, just like education, is already starkly divided for the poor and the rich: a wealthy defendant may well have a whole team of people working full time on their case, while poor defendants will be lumped in with a dozen others on a public defender’s docket. AI legal assistants and AI legal search engines will likely lower the wages for paralegals (who are being deskilled). “Ambulance chasers” and “sharks” will increase their dominance of the low-end market, cutting costs due to AI, while also undermining quality. Competitive pressures mean that honest and dishonest lawyers alike will have to take on the absolute maximum number of cases that can be done in a certain amount of time. Those lawyers who genuinely care about serving the underserved will suffer from the increasing pressures of this competition in their market: AI-assisted competition will drive up the numbers of cases these lawyers have to take on, and drive down the quality that they can afford to provide. Meanwhile, wealthy clients and corporations will be largely unaffected, since they will continue to be served by law firms whose services are way out of reach for almost everyone else.

In the realm of coding, big tech companies will continue to pay high wages to those who produce code for high stakes situations, where even small optimizations can be worth a lot of money. But an increasing number of programmers will be subjected to competition from companies that provide minimal training (say, a four-week course in using generative AI for programming), and that treat their workers as replaceable and disposable, gigifying and deskilling ever more coding work.

In sum, in many of the domains where generative AI may play a major role, we think the effects of AI automation and deskilling will likely be an acceleration, intensification, and spreading of tendencies that we can already observe today, such as gigification: it will make low quality work somewhat worse, but much cheaper, thus creating downward pressure on wages and quality alike, while putting high quality work increasingly out of reach. Out of reach, both for all those workers who would much rather do such work, and for those consumers who cannot afford to buy anything but things and services produced in AI-assisted contexts.

(Why We Fear AI, Chapter 4)

So, back to our original question – does AI actually work? I think the tradeoff graph – along with its interpretation in terms of Ikea, fast fashion and deskilling – provides a better way of asking the question, and a better answer than “yes” or “no”. It works to change the cost-quality tradeoff, with quite definite effects, and that makes AI a particular kind of tool: a tool not just for production, but also for crushing wages. It’s for increasing the power of those that pay wages/salaries/etc vis-a-vis those that earn them. It “works” by working only on the lower-quality side of the cost-quality tradeoff, and that is precisely what allows it to work as a tool of deskilling. AI isn’t some neutral tool – it’s a weapon of class war from above. It’s crucial to be clear about this: the development of technology under capitalism is never simply about productivity, but about tradeoffs, and ultimately about power. A tool can be inherently anti-worker and anti-consumer. It’s still true, then, as the debunkers rightly have it, that we shouldn’t believe the tales of golden ages “so unbelievably good that I can’t even imagine” (ala Sam Altman). But we should focus on what the technology is actually for, and simply debunking their claims can leave us with the mistaken idea that AI will turn out simply useless. The cybernetician Stafford Beer said somewhere that there is “no point in claiming that the purpose of a system is to do what it constantly fails to do”. I think that rhymes well with Ali Alkhatib’s point that we should think about AI as a political project through and through. We should start by asking what it is that AI actually does, rather than getting sucked into constant arguments about what it can’t do. And I hope thinking about speed-accuracy tradeoffs can be one little tool to complicate the question of “does it work” in a way that helps to clarify the political project. And perhaps we can even, through clarifying the class (war) nature of that project, understand something about capitalism and the political moment we find ourselves in right now.